Into The Ocean

Why did I rethink my career in science? From the streets of Germany to the Cambodian rainforests

I stood there looking down at the water, it was dark, with only faint artificial light illuminating the surface.

The water flowed steadily with the current through the mangroves and dragged with it humanities greatest disgrace.

Floating along the surface was plastic rubbish ‑ various bottles, containers, and wrappers, all being pulled out to

sea. I wondered what would be the fate of this plastic, would it end up in the stomach of a whale perhaps? Maybe the

smaller pieces inside turtles or sea birds? Would we find it at the bottom of the ocean or washed up on a beach

somewhere 100 years from now? I don't know, what I do know is that night was profound for me, because of what

occurred afterwards, and because of my experience the previous two weeks...

I had never been to Europe and was beyond excited to experience what had been described to me by so many friends. I

was never quite prepared for just how many people there would be. I arrived in Berlin, Germany on a sunny afternoon,

I admired the Bavarian style buildings, had a bite to eat then slept off the jetlag and over 24 hours of travel on

busy aeroplanes. The next day I explored on foot and navigated the hordes of people admiring the various memorials,

and monuments. I paid a visit to the Berlin wall art and drank the local beer. All in all, a fine Europe experience.

The reason I was in Berlin was because of the Lindau Nobel Laureate meetings, which I have spoken about in previous

blogs and with support from the Academy of Science and the Science and Industry Endowment Fund, I was fortunate to receive

an insight into the research and innovation in Germany prior to making my way to Lindau. This tour was very interesting,

the level of research and support for innovation was incredible to see, not to mention the high calibre of equipment and

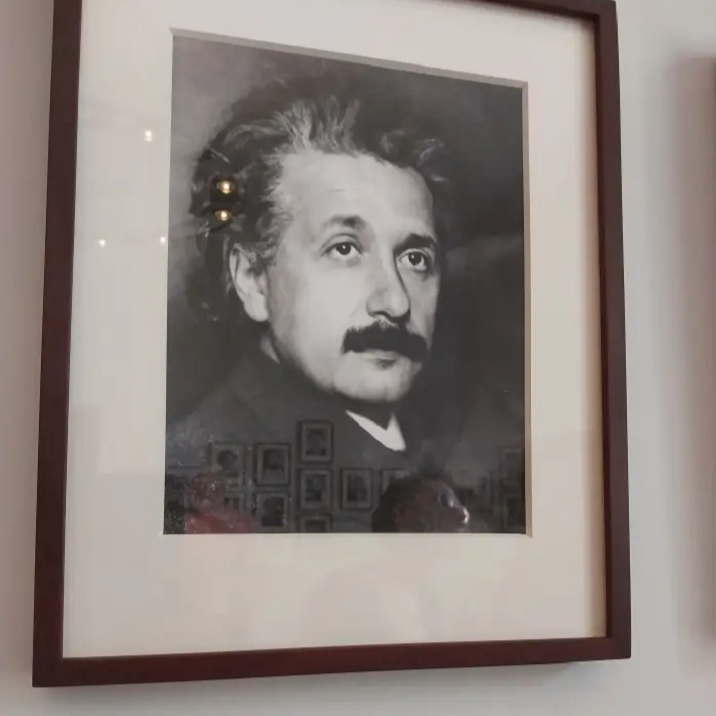

staff on hand to explain everything to us. One institution we visited had paid host to the likes of Albert Einstein and

other bright minds. It felt surreal to stand where they stood and to absorb the seriousness of these research institutes,

knowing the results they produced were changing the world.

Onwards to Lindau, I was already highly absorbed in scientific discussion and feeling enthused about continuing my career

towards innovative science and making a change in the world. Arriving in Lindau was surreal, it was a beautiful sunny day,

there were cobblestone streets and beautiful old buildings. It was truly picturesque for how I had imagined Europe,

including a lake with the clearest water in view of theSwiss alps. I pinched myself every day that I was in Lindau to

remember that it was real, and I had finally made it. The meeting itself did not disappoint and stands as the highlight

of my scientific career to date. Being an environmental scientist attending a meeting on chemistry, I thought I would

find it hard to collaborate and engage with the other young scientists. I couldn't have been more wrong. I developed

collaborations and friends across continents and disciplines and realised that the pursuit of knowledge is universal,

as is the desire to make positive changes to the world. This was evident across both young scientists and Nobel laureates

as, when you have passion for your work, and genuinely want to make a positive change, its a universal language that

brings people together. Being able to fully appreciate the value of this experience was difficult at the time, I was

overcome with emotion at having to say goodbye to everyone at the end of the meeting all the while realising something

I had looked forward to for so long had ended. All good things do have to end and I have the memories, experiences and

friendships to last. Leaving Lindau was not the end of this experience however, not by far.

I flew out from Munich and landed in Singapore, being already acclimatised to the European summer, I did not find the

characteristic blast of humid air stepping out of the airport overly discomforting. I was grateful to be in Singapore

and still on a high from my epic three-week stint in Germany. Singapore was just a stopover to my real destination which

was Cambodia. I was headed there as part of the University of Adelaide science3500 study tour which took a select group

of undergraduate students to experience Cambodia in all its wonders and environmental issues such as land clearance,

exploitation, and animal trafficking. I was fortunate to attend a similar study tour in my final undergraduate year and

the experiences I gained were life changing. Being on the other end of this tour as a teaching assistant, and getting to

watch the same life changing experiences happen in the students was very exciting for me. I was not, however, prepared

for how confronting I would find this post-covid version of Cambodia and that this second visit would have such an impact

on me.

Landing in Phnom Penh was so exciting, the city is a buzz, so much traffic, colour and people. I was reminder of the

characteristic sound of car horns signalling that someone is about the drive past, not that they are annoyed at your

driving (like in Australia). Phnom Penh was short lived, and our first real Cambodia experience came in the form of a

home stay in floating villages on Tonle Sap River. These villages use bamboo or empty drums under their house so that they

float on the water and during the wet season all the boats need to be securely tied down so that the houses do not float

away with the influx of water. These houses are a huge change to the lavish styled homes I observed in Berlin and Lindau,

they are built by hand using the materials available and comprise usually one large room and a bathroom (long drop). The

people here rely heavily on fishing the river to sustain themselves and make a living. They also weave baskets and bags from

an invasive river plant (water hyacinth) and farm crocodiles, rice (behind the river houses), chilli, fruits and

vegetables. The students helped the villagers set up fishing nets and collected them at the break of dawn the next day.

The type of fish caught was rather eye opening, anywhere else they would have been thrown back into the river as being far

too small and yet here they were kept, there wasn't another choice. When it's a decision between eating that day and ensuring

the fish population is sustained, you can be sure they will choose the former ‑ I would. If this wasn't enough the crocodile

farming was another intense experience. Here we had an apex predator, evolved over millions of years to be the perfect predator

and we reduced them to cages and their babies to buckets. I say we, because this is not fault of the Cambodian people, we,

in our privileged lives have the blame. These people have no alternative way to find income and support their families, and

we don't help and then are abhorred they do these things. These crocodiles also used to sell for $1000 USD but after COVID

they are only selling for $40 USD. This is an unbelievable drop in price, that is devastating for the people relying on this

income. All this in just the first few days of being here... on a happier note the visit to Angkor Wat after the village stay

showcased another side of Cambodia, and while it was the more touristy side it was stunning and a nice moment away from the

environmental issues.

Cambodian people are the best part of the country, they are so friendly and I really enjoyed getting to know some of the

locals. Cambodian people took COVID very seriously and all wore masks in public places, despite the very low case numbers

that they were experiencing. Most of the people were vaccinated with mobile medical units heading out the villagers to

vaccinate the people there. This is a stark contrast to what I observed in Germany, who have one of the lowest public uptakes

of vaccination in the world and masks are no longer mandated, so nobody in the public wore one. It was shocking and

frustrating to witness this difference between such a wealthy country compared to one so poor. This probably contributed

more to my love of the Cambodian people. After Tonle Sap, we ventured into another village stay but this time in the Cardamom

Mountains. It is hard to put into words what I experienced and felt there. Leading up to the stay, I envisaged we would be

sleeping in the jungle, I had taken malaria medication for this reason. We drove up to this village and there was no jungle,

it had all been cleared. All we saw was a lot of mud roads and so many vehicles and buildings being constructed. There were

eco-tourism stays being set up to bring tourists in once travel had resumed to pre-covid levels. We were the first group to

experience this newly developed area. Covid had driven people out of the cities in search of work. With the shutdown of

tourism many people were left without a source of income. There wasn't another option other than clearing forest to make

way for agriculture and start exporting food for profit. Agriculture also means the application of insecticides and to

highlight the impact of this, I slept outside without a mosquito net and did not get bitten once. Probably didn't need the

Malaria tablets after all. There was no sound of insects, a tropical forest should be teeming with insects, so loud that

it's hard to sleep, but it was dead quiet. I will never forget the silence.

The weird thing was, I wasn't sad that the forest had been cleared, I was sad because it had to be done. The actual act of

deforestation comes from a different place than wanting to destroy the forest. It comes from a place of survival. Clearing

this forest and setting up agriculture meant families could be fed and people could survive ‑ should we then be mad that

they did this? We who sit comfortable in our homes on land that was cleared long ago. I found this internal struggle

difficult and upon heading out further into the actual jungle I got a clearer picture of what had been lost. These forests

are incredible, there is so much diversity in such a small area and so much life. The thought of losing all of this is

heartbreaking. How do we balance keeping people fed and comfortable and yet also maintain these precious resources? In a

country like Cambodia, they are fighting this struggle every day. The local people I spoke to appreciate the value of

the environment and want badly to do better but don't have the resources to do so. This was never more apparent than the

experience I had on an island off the coast of Cambodia. We arrived here with the students to learn about coastal marine

impacts in Cambodia due to land clearing, nutrient run off and climate change. This was where the anecdote at the beginning

of the story comes in ‑ watching all that rubbish float by.

Speaking to a local I found out that there is no waste removal system in Cambodia. There is no way to dispose of the plastic

waste. We get our bins collected and the rubbish goes to landfill, imagine that you don't have that, how would you dispose

of your waste? There was a notice board in Tonle Sap that said local people used to wrap food in banana leaves and that

disposing of these into water bodies was normal, as it would break down. With the uptake of plastic packaging this same

disposal technique is used, there is not enough education around the issues with plastic waste, although this is improving.

The combination of inadequate waste disposal and lack of education culminated in that pile of rubbish floating past me. I

felt intense emotion at this point. After my expedition to Germany, learning about all the research that was being done

both there and around the world and yet here in Cambodia, the simple issue of waste removal hadn't been addressed. As a

scientist, was I working to tackle problems that were too big when the real issues were right here in front of me and

could be tackled today? The next day, while at lunch, we received a message, the village chief had listened to us discuss

the plastic rubbish issue and had rounded up the entire village to start cleaning up the island. I was speechless, after

feeling such hopelessness the night before, suddenly I felt hope. People want to make a change, they want to make this

world better, no matter where they come from and as people, we have the power to do so.

Reflecting on this trip there are so many issues that still need to be addressed in Cambodia, but the people want to do

right, and it is up to us to help them. Developing ways to live sustainable with the land and ensuring an income and

livelihood for all people, creating mechanisms of waste removal and possible ways to generate income on plastic waste.

These are just some things that we can work on, and people already are. These are some fantastic organisations doing

incredible work in Cambodia (Wildlife Alliance, ACCB). The juxtaposition of the two opposing worlds that I experienced,

the science elite in Germany and the people of Cambodia, were not as different as I thought, prior to embarking on this

journey. In fact, the passion and desire to be better and make the world better, was reflected in all the people I met,

regardless of their background. I realised that there is a disconnect between some of the problems science is working to

solve and some problems that could be solved right now. I love science and the pursuit of knowledge should be a driving

force for humanity, however, this trip made me feel like sometimes, as scientists, we lose sight of what is important and

become out of touch with the real world. The race to publish, get grants and win prizes overshadows the ability to

actively participate in the world and bring about positive change in the here and now. I don't have an answer for how we

can do better, but this experience did make me reflect on the type of scientist that I want to be.